Entries Tagged 'reading' ↓

December 2nd, 2017 — reading

When Late-19th Century Daughters Remember The Fiddles of their Fathers

The other day I was doing some background research on my grand-grandfather by reading Emma Guest Bourne’s (1882-1959) A Pioneer Farmer’s Daughter of Red River Valley, Northeast Texas (1950) and came across this poignant passage:

Father used to play a piece on his violin known as Blossom Prairie. I caught a few words as I would hear him singing the song, but have never heard the song since I was a child, and only know a few words. Yet the melody is still with me. In my imagination, I can see father as he sat before the fireplace in his little straight chair with his violin and bow as he played this beautiful song. At intervals he would let the bow rest as it was poised over the violin, and he would thump the melody of the chorus with his left fingers as he held the violin under his chin. In the chorus, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, were the opening words, and then these words would follow; [sic] “Oh, the green grass grows all over Blossom…†How I have wished for these words, but no one has even been able to give them to me. Mount Vernon was the county seat for several years of Lamar County before the seat was established at Paris, five miles north of Mt. Vernon. [1]

Bourne was born in 1882, and her longing for a ghost-song of her father initially reminded me of the early days of file-sharing on the internet–when one may have heard a song only once in one’s life, and never knowing the name, was somehow able to find it on Napster or by similar means.

But upon reflection, what Bourne’s passage reminded me of was a similar scene told by Laura Ingalls Wilder’s (1867-1957) daughter Rose Wilder Lane (1886-1968) of her last visit to her grandparents “Ma and Pa Ingalls”:

We were ready to start early next day, before sun-up, and that evening we went to Grandma’s to say good-by….

Aunt Carrie and I sat in the doorway. Papa got up to give Grandma his chair and Mama stood a minute in the doorway to the dark sitting room. They had blown out the lamp, and there was just a faint start-shine that seemed to be more in the summer air than in the sky. Then, Mama said, “Pa, would you play the fiddle just one more time?â€

“Why yes, if you want I should,†Grandpa said. And then he said, “Run get me my fiddle-box, Laura,†and somehow I knew that he had said those words in just that way, many times, and his voice sounded as if he were speaking to a little girl, not Mama at all. She brought it out to him, the fiddle-box, and he took the fiddle out of it and twanged the strings with his thumb, tightening them up. In the dark there by the house wall you could see only a glimmer in his eyes and the long beard on his shirtfront, and his arm lifting the bow. And then out of the shadows came the sound. It was—I can’t tell you. It was gay and strong and reaching, wanting, trying to get to something beyond, and ti just lifted up the heart and filled it so full of happiness and pain and longing that it broke your heart open like a bud.

Nobody said anything. We just sat there in the dimness and stillness, and Grandpa tightened up a string and said, “Well, what shall I play? You first, Mary.†And from the sitting room where she sat in her rocker just inside the doorway, Aunt Mary said, “ ‘Ye banks and braes of Bonnie Doon,’ please Pa.â€

So Grandpa played. He went on playing his fiddle there in the warm July evening, and we listened. In all my life I never heard anything like it. You hardly ever heard anymore the tunes that Grandpa played…. [2]

NOTES

[1] Emma Guest Bourne, A Pioneer Farmer’s Daughter of Red River Valley, Northeast Texas, (Dallas, TX: The Story Book Press, 1950), 262.

[2] Rose Wilder Lane, “Grandpa’s Fiddle,â€A Little House Sampler, by Laura Ingalls Wilder and Rose Wilder Lane, ed. William Anderson, (Lincoln, NE, 1988; New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1995), 66-67.

November 26th, 2017 — reading

Reading About AI and All That

Reading About AI and All That

Three interesting pieces on AI and its potential malevolence or benevolence:

November 25th, 2017 — reading

The Trouble with Reading Too Many Good Books

Twenty-four years ago, Harold Bloom said we should read only canonical works, only the best of the best:

Who reads must choose, since there is literally not enough time to read everything, even if one does nothing but read….

Reviewing bad books, W. H. Auden once remarked, is bad for the character. Like all gifted moralists, Auden idealized despite himself, and he should have survived into the present age, wherein the new commissars tell us that reading good books is bad for the character, which I think is probably true. Reading the very best writers–let us say Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Tolstoy–is not going to make us better citizens. Art is perfectly useless, according to the sublime Oscar Wilde, who was right about everything. He also told us that all bad poetry is sincere….

Reading deeply in the Canon will not make one a better or a worse person, a more useful or more harmful citizen. The mind’s dialogue with itself is not primarily a social reality. All that the Western Canon can bring one is the proper use of one’s own solitude, that solitude whose final form is one’s confrontation with one’s own mortality.

We possess the Canon because we are mortal and also rather belated. There is only so much time, and time must have a stop, while there is more to read than there ever was before…. One ancient test for the canonical remains fiercely valid: unless it demands rereading, the work does not qualify….

Yet we must choose: As there is only so much time, do we reread Elizabeth Bishop or Adrienne Rich? Do I again go in search of lost time with Marcel Proust, or am I to attempt yet another rereading of Alice Walker’s stirring denunciation of all males, black and white? ….

If we were literally immortal, or even if our span were doubled to seven score of years, says, we could give up all argument about canons. But we have an interval only, and then our place knows us no more, and stuffing that interval with bad writing, in the name of whatever social justice, does not seem to me to be the responsibility of the literary critic…. [1]

More recently, Alan Jacobs has suggested we should place some limits even on canonical works:

While I agree with Harold Bloom about many things and am thankful for his long advocacy for the greatest of stories and poems, in these matters I am firmly on the side of Lewis and Chesterton. Read what gives you delight—at least most of the time—and do so without shame. And even if you are that rare sort of person who is delighted chiefly by what some people call Great Books, don’t make them your steady intellectual diet, any more than you would eat at the most elegant of restaurants every day. It would be too much. Great books are great in part because of what they ask of their readers: they are not readily encountered, easily assessed. The poet W. H. Auden once wrote, “When one thinks of the attention that a great poem demands, there is something frivolous about the notion of spending every day with one. Masterpieces should be kept for High Holidays of the Spiritâ€â€“–for our own personal Christmases and Easters, not for any old Wednesday. [2]

Excess is toxic. Too much of anything is biologically poisonous. One might compare the worldview of the steady reader to the worldview of the career soldier. Take General John J. Pershing (1860-1948) for example:

He liked life at McKinley. With a good Officers’ Club and a large contingent of officers, it furnished a social world all its own. Pershing made it a point, however, to avoid concentrating on Army friendships. “We Army people tend to stick together too much and become clannish,†he said. “It’s good to know civilians. It helps them appreciate what the Army is like and it’s good for us to know what they’re like.†[3]

It was Pershing’s ability to get outside his own habitual worldview as a career soldier and actively intermingle with civilian life and culture that led him to further successes. At one point, when he was stationed in the Philippines:

Pershing was thunderstruck. To his knowledge, this was unprecedented. He had never heard of a white man being so honored by Moros [as Pershing had]. Solemnly he thanked Sajiduciman. In a concluding ceremony, both men placed their hands on the Koran and swore allegiance to the United States. [4]

NOTES

[1] Bloom, Harold, The Western Canon: the Books and School of the Ages, (New York, NY: Harcourt Brace, 1994) 15–16, 30–32.

[2] Jacobs, Alan, The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction, (New York, NY: Oxford UP, 2011) 23.

[3] Smythe, Donald, Guerrilla Warrior: the Early Life of John J. Pershing, (New York, NY: Scribner’s Sons, 1973) 135.

[4] Smythe, Guerrilla Warrior: the Early Life of John J. Pershing 92.

November 20th, 2017 — reading

Disenchantment

Disenchantment with rhetoric about law that ignores legal realities:

A very important think piece by Jesse Singal: “There Have Been So Many Bad Lefty Free-Speech Takes Lately,” New York Magazine, November 12, 2017.

Disenchantment with the beltway culture that ignores any reality:

A poignant reflection on Washington, D.C. and writing by Tom Ricks: “Babylon Revisited: Melancholy Thoughts After a Short Trip to Washington, D.C.,” Foreign Policy, November 17, 2017.

“Disenchantment,” in Max Weber’s (1864-1920) words, means:

The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the ‘disenchantment of the world.’ Precisely the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life either into the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations. It is not accidental that our greatest art is intimate and not monumental, nor is it accidental that today only within the smallest and intimate circles, in personal human situations, in pianissimo, that something is pulsating that corresponds to the prophetic pneuma, which in former times swept through the great communities like a firebrand, welding them together. If we attempt to force and to ‘invent’ a monumental style in art, such miserable monstrosities are produced as the many monuments of the last twenty years [1897–1917].

Elaborating on Weber’s term, “disenchantment,†Richard Jenkins notes:

It is the historical process by which the natural world and all areas of human experience become experienced and understood as less mysterious; defined, at least in principle, as knowable, predictable and manipulable by humans; conquered by and incorporated into the interpretive schema of science and rational government. [1]

Yet, Jenkins points out, there may not be anything necessarily “modern†about this disenchantment:

Even if we disregard the rich variety of communities and ethnies in the pre-modern world, there is every reason to suggest that the European world, at least, has been disenchanted, in the sense of epistemically fragmented, for as long as we can perceive it in the historical record.[2]

NOTES

[1] Jenkins, “Disenchantment, Enchantment and Re-Enchantment: Max Weber at the Millennium,†Max Weber Studies 1 (November 2000): 11–32 at 12; Weber, “Science as a Vocation,” From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, Translated and eds. H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills. (New York, NY: Oxford UP, 1958) 55.

[2] Jenkins, “Disenchantment, Enchantment and Re-Enchantment: Max Weber at the Millennium†15.

November 9th, 2017 — reading

The Greatness of Russia and the Greatness of Texas

Russians call World War II, “The Great Patriotic War,†and Dr. Victor Davis Hanson, whom I almost never agree with, has a decent article out today acknowledging Russian greatness/sovereignty (derzhavonst/державонÑÑ‚), writing:

This Veterans Day, we should also remember those heroic Russian soldiers. In bitter cold, and after losing hundreds of thousands of lives, they finally did the unbelievable: They halted the march of Nazi Germany. [1]

What do I mean by Russian greatness? I mean things like:

Putin’s favorite quote these days is, “We do not need great upheavals. We need a great Russia.â€[2]

As Nina Kruscheva, daughter of Nikita Khrushchev, has recognized:

Putin maintains that Russia’s problem today is not that we, the Russians, lack a vision for the future but that we have stopped being proud of our past, our Russian-ness, our difference from the West. ‘When we were proud all was great, he said at the Valdai International Discussion Club meeting last September. While he may bemoan the death of the Soviet state, Putin’s search for greatness extends even further back in history, to Byzantine statehood…. Why is Putin’s idea of going back to the future attractive for Russians? …. But our [Russia’s] problem is that our idea of greatness doesn’t involve such small stuff. It is extreme, everything or nothing.[3]

I find Russian greatness comparable to Texas and its culture of greatness:

If one southerner can whip twelve Yankees, how many Yankees can six southerners whip? Although the premise of this problem seems to have been somewhat unstable, it evidences a spirit of confidence that for a long time seemed lost to the New South. It may be, however, that the aggressiveness and boastfulness so characteristic of the Old South instead of dying out after the war simply followed the trail of cotton and migrated to Texas. From the time they annexed the United States in 1845 until their recent singlehanded and unaided [“not so fast,” said the Russian veteran!] conquest of Germany and Japan, Texans have been noted for their aversion to understatement. But it is possible that when Texans talk “big†they are speaking not as Texans but as southerners. Certainly, that Texan was speaking the language of the Old South when he rose at a banquet and gave this toast to his state: “Here’s to Texas. Bounded on the north by the Aurora Borealis, bounded on the east by the rising sun, bounded on the south by the precession of the equinoxes, and on the west by the Day of Judgment.†[4]

And:

“That’s why I like Texans so much … They took a great failure [the Alamo] and turned it into inspiration… as well a tourist destination that makes them millions.â€[5]

NOTES

[1] Victor Davis Hanson, “Remembering Stalingrad 75 Years Later,†National Review, November 9, 2017.

[2] Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy, “Putin and the Uses of History,†The National Interest, 117 (January–February 2012) 21–31 at 23.

[3] Nina L. Krushcheva, “Inside Vladimir Putin’s Mind: Looking Back in Anger,†World Affairs, 177 (July–August 2014): 17–24 at 19, 20.

[4] Robert S. Cotterill, “The Old South to the New,†Journal of Southern History, 15 (February 1949): 3–8 at 8.

[5] Robert T. Kiyosaki Rich Dad Poor Dad: What the Rich Teach their Kids About Money that the Poor and Middle Class Do Not, (Scottsdale, AZ: Plata Publishing, 2011) 132.

October 31st, 2017 — reading

Initial Thoughts on the Breech between Digital and Analog

The steam engine with a governor provides a typical instance of one type, in which the angle of the arms of the governor is continuously variable and has a continuously variable effect on the fuel supply. In contrast, the house thermostat is an on-off mechanism in which temperature causes a thermometer to throw a switch at a certain level. This is the dichotomy between analogic systems (those that vary continuously and in step with magnitudes in the trigger event) and digital systems (those that have the on-off characteristic).

––Gregory Bateson (1904–1980)[1]

While Baylor University is not my alma mater, its Distinguished Professor of Humanities Alan Jacobs has been my teacher for the past few years. While I did not formally audit Jacob’s course this semester “Living and Thinking in a Digital Age,†I did recently finish the principal texts: Kevin Kelly’s The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces that Will Shape Our Future (2016) and The Revenge of Analog: Real Things and Why They Matter (2016) by David Sax.

What follows are initial thoughts only. I intend to think more about these books and write something more in depth soon enough.

Initial thoughts on Kelley: While it’s a Penguin paperback, the aesthetics of the book are wanting: pretty bland for a book told in such a cheerleading tone––just flat white pages printed with what looks like Times New Roman––as if it were a newspaper. Was this irony intentional? On the other hand, unless I’m a sucker for novelty (and I am), Kelly’s twelve trends in emerging technologies came across to the present writer, for the most part, as an interesting essay with many things to think about. Whether or not one agrees with the “inevitableness†of Kelly’s thesis, there are things to ponder further. But its cheerleading tone seems similar to feelings held by students whom Leo Strauss (1899–1973) once addressed:

We [moderns] somehow believe that our point of view is superior, higher than those of the greatest minds [of the ancient world]––either because our point of view is that of our time, and our time, being later than the time of the greatest minds, can be presumed to be superior to their times; or else because we believe that each of the greatest minds was right from his point of view but not, as be claims, simply right: we know that there cannot be the simply true substantive view but only a simply true formal view; that formal view consists in the insight that every comprehensive view is relative to a specific perspective, or that all comprehensive views are mutually exclusive and none can be simply true. [2]

Initial thoughts on Sax: With its hardcover, Baskerville font, cream-colored pages, and embossed dustjacket, I regard this book very highly in terms of aesthetics. Its contents, however, aren’t (at least initially) very captivating. Then again, maybe this was because (1) I was born in the analog era, so much of Sax’s book is review for me, and (2), because it’s review––by definition––it cannot be novel. Nonetheless, I found the most interesting portion to be Chapter 7 “The Revenge of Work†because here Sax (unlike Kelly) doesn’t explain his pattern finding in the voice of a utopian cheerleader. While Chapter 7 discusses Shinola watches made in Detroit in a hopeful manner, Sax’s writing remains quite sober and never pretends to offer easy answers.

Initial thoughts on reading and writing: Both Kelly and Sax write in a “breezy†style suitable for airport consumer readers—a strong contrast to say, Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age (2007) where readers find a much slower-paced “storytellingâ€[3] style that demands reflection, review, rereading, and repetition.

Initial thoughts on technology: In the spirit of neo-analogic Zeitgeist, I confess I wrote the first few drafts of this blog post by hand (as I often do). I also printed Jacob’s syllabus for the “Living and Thinking in a Digital Age†course and read through it. Then, with regard to reading the books by Kelly and Sax and writing about them, I physically underlined what I thought were the important parts of the syllabus:

How is the rise of digital technologies changing some of the fundamental practices of the intellectual life: reading, writing, and researching? ….  So we will also spend some time thinking about the character and purposes of liberal education…. This is a course on how the digital worlds we live in now — our technologies of knowledge and communication — will inevitably shape our experience as learners. So let’s begin by trying to get a grip on the digital tech that shapes our everyday lives.

Finally, to find the quotations I needed, I consulted my previous digital notes on Strauss and Bateson, then copied-and-pasted where appropriate.

Initial thoughts on spirituality: (1) When I first came across Kelly’s line––

[Google] takes these guesses and adds them to the calculation of figuring out what ads to place on a web page that you’ve just arrived at. It’s almost magical, but the ads you see on a website today are not added until the moment after you land there. (181)

––it reminded me of an observation from the atheist anthropologist Gregory Bateson:

My view of magic is the converse of that which has been orthodox in anthropology since the days of Sir James Frazer. It is orthodox to believe that religion is an evolutionary development of magic. Magic is regarded as more primitive and religion as its flowering. In contrast, I view sympathetic or contagious magic as a product of decadence from religion; I regard religion on the whole as the earlier condition. I find myself out of sympathy with decadence of this kind either in community life or in the education of children.[4]

(2) Kelly’s last line of his book––“The Beginning, of course, is just beginning,†(p. 297)––seems highly suggestive, perhaps because it seems highly biblical. But it might also be a tip of the hat to Joycian recourse. If digital technologies and patterns are as inevitable as Kelly says they are, then Analog’s Wake might’ve made for a more appropriate title.

More to come.

NOTES

[1] Mind and Nature, (New York, NY: E. P. Dutton, 1979) 110–11.

[2] “What is Liberal Education?†Address Delivered at the Tenth Annual Graduation Exercises of the Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults. June 6, 1959.

[3] With regard to “storytelling,†early in his magnum opus, Taylor writes:

I ask the reader who picks up this book not to think of it as a continuous story-and-argument, but rather as a set of interlocking essays, which shed light on each other, and offer a context of relevance for each other…. I have to launch myself into my own story, which I shall be telling in the following chapters… One important part of the picture is that so many features of their world told in favour of belief, made the presence of God seemingly undeniable. I will mention three, which will place a part in the story I want to tell….. And at this point I want to start by laying out some broad features of the contrast between then and now, which will be filled in and enriched by the story. (A Secular Age, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP) ix, 21, 29)

[4] Gregory Bateson and Mary Catherine Bateson, Angels Fear: Towards an Epistemology of the Sacred, (Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press Inc., 2005) 56.

October 27th, 2017 — reading

Reading about Russia on Friday

Via Catapult.co, Sabrina Jaszi translated a short story “Bluebells” from руÑÑкий to English (for the first time!), written in the late 1950s-1960s by Reed Grachev (1935-2004).

Also, Scott Neuman reports on “Documents offer Insight into Soviet View of JFK Assassination,” NPR.org, October 27, 2017.

Although, on this particular issue, I think it best to turn to Norman Mailer’s (1923-2007) investigation Oswald’s Tale (1995).

October 11th, 2017 — Books, reading

The Life of Books in 18th Century Autobiography

From the Autobiography (1795) of Edward Gibbon (1737-1794):

It is whimsical enough, that as soon as I left Magdalen College my taste for books began to revive; but it was the same blind and boyish taste for the pursuit of exotic history. Unprovided with original learning, unformed in the habits of thinking, unskilled in the arts of composition, I resolved—to write a book.

From the Autobiography (1731?) of Giambattista Vico (1668-1744):

In a conversation which he had with Vico in a bookstore on the history of collections of canons, he asked him if he were married. And when Vico answered that he was not, he inquired if he wanted to become a Theatine. On Vico’s replying that he was not of noble birth, the father answered that that need be no obstacle, for he would obtain a dispensation from Rome. Then Vico, seeing himself obliged by the great honor the father paid him, came out with it that his parents were old and poor and he was their only hope. When the father pointed out that men of letters were rather a burden than a help to their families, Vico replied that perhaps it would not be so in his case. Then the father closed the conversation by saying: “That is not your vocation.â€

—The Autobiography of Giambattista Vico, translated by Max Harold Fisch & Thomas Goddard Bergin, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1944) 134-35.

October 9th, 2017 — reading

Spending Sundays with Susan Sontag

Spending Sundays with Susan Sontag

Rebecca Chace’s “Regarding the Pain of Trump” in the Los Angeles Review of Books, September 30, 2017, has several nods and references to Susan Sontag. And I was reading some Sontag these last two weeks: Where the Stress Falls (2001) and At the Same Time (2007), and came across this observation in the latter book:

The writer in me distrusts the god citizen, the “intellectual ambassador,†the human rights activist—those roles which are mentioned in the citation for this prize, much as I am committed to them. The writer is more skeptical, more self-doubting, than the person who tries to do (and to support the right thing).  –“Literature is Freedomâ€

October 7th, 2017 — reading

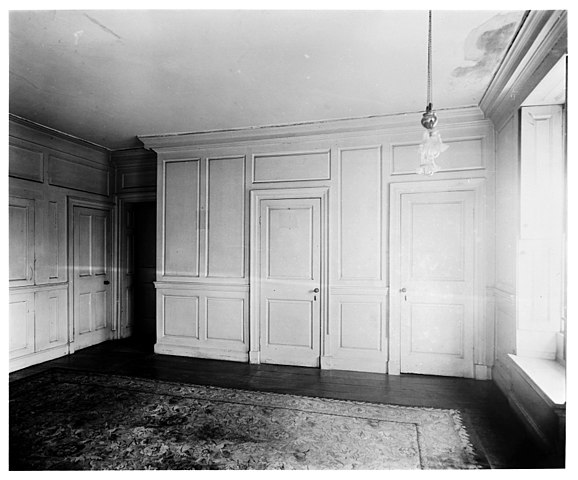

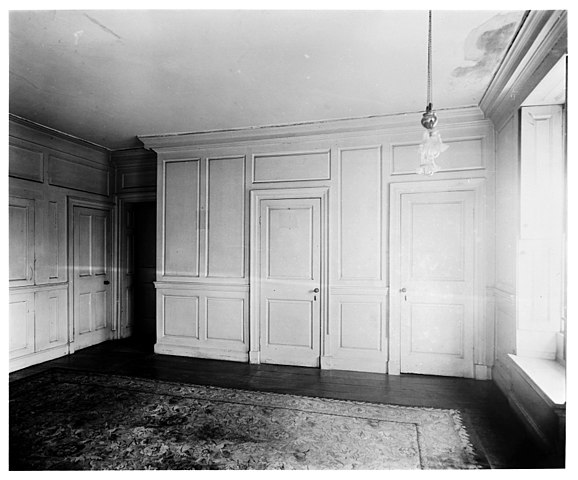

A Pair of Thoughts on Empty Rooms

Upton House (Joseph Lister/Wikicommons)

First from the Irish writer James Stephens (1880-1950):

At last the room was as bare as a desert and almost as uninhabitable. A room without furniture is a ghostly place. Sounds made therein are uncanny, even the voice puts off its humanity and rings back with a bleak and hollow note, an empty resonance tinged with the frost of-winter. There is no other sound so deadly, so barren and dispiriting as the echoes of an empty room. The gaunt woman in the bed seemed less gaunt than her residence, and there was nothing more to be sent to the pawnbroker or the secondhand dealer.

–The Charwoman’s Daughter, (London: Macmillan & Co., 1912) “Ch. XVI,” 100.

Next, 102 years later, from Wilfred M. McClay of the University of Oklahoma:

An ordinary but disquieting phenomenon: the translation of place into space—the transformation of a setting that had once been charged with human meaning into one from which the meaning has departed, something empty and inert, a mere space. We all have experienced this, some of us many times. Think of the strange emotion we feel when we are moving out of the place where we have been living, and we finish clearing all our belongings out of the apartment or the house or the dorm room—and we look back at it one last time, to see a space that used to be the center of our world, reduced to nothing but bare walls and bare floors. Even when there are a few remaining signs of our time there—fading walls pockmarked with nail holes, scuffs in the floor, spots on the carpet—they serve only to render the moment more poignant, since we know that these small injuries to the property will soon be painted over and tided up, so that in the fullness of time there will be no trace left of us in that spot.

–“Introduction: Why Place Matters.†Why Place Matters,

Edited by McClay and Ted V. McAllister, (New York, NY: New Atlantis Books, 2014) 4.