September 26th, 2017 — reading

The Religious Diplomacy of Joseph P. Kennedy

Religion is opinions and actions, determined and restricted with stipulations and prescribed for a community by their first ruler, who seeks to obtain through their practicing it a specific purpose with respect to them or by means of them.

––Al-Farabi (872–951 AD), The Book of Religion[1]

Al Smith’s presidential loss in 1928 and Jack Kennedy’s Houston speech in 1960 concerning religion and government have both been run through the ringer aplenty. There are shelfs and stacks of books that compare and contrast (and exhaust) those two events, and I’m honestly not very interested in reading more about them.

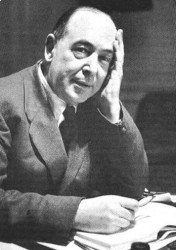

But after reading Robert Dalleck’s A Life Unfinished: John F. Kennedy, 1917–1963 (2001), I was struck that the most interesting character was Kennedy’s father Joseph Patrick Kennedy.

So soon enough I began reading David Nasaw’s The Patriarch: the Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy (2012), and soon enough, I came upon these two quite remarkable passages:

Opposing or remaining neutral to Jack’s candidacy, as the church leaders now appeared to be doing, was, Kennedy believed, a betrayal not only of him, his son, and his family, but of the millions of American Catholics who stood to benefit from the election of one of their own to the presidency of the United States. For perhaps the first time in his life, certainly for the first time since the death of Joe Jr., Joseph P. Kennedy was forced to reconsider, to reevaluate, the ties that bound him to his church. “My relationship with the Church will never be the same,†he confessed to Galeazzi in an April 17 letter,†and certainly, never the same with the hierarchy. But that will not make any difference to them, I am sure, and I can assure you that it will not make any difference to me. For the last few years which I have left, I will indulge myself at least in continuing to believe that friends are friends when you need them. Please do not be upset yourself about my attitude. I would not want anything to annoy you.†[2]

And:

[Billy] Graham, on arriving at the Palm Beach house in mid-January, was greeted by the president-elect. “My father’s out by the pool. He wants to talk to you.†At poolside, the two shook hands, then Kennedy, Graham recalled in his autobiography, “came straight to the point: ‘Do you know why you’re here?’ †Kennedy told the evangelist (and Nixon supporter) that he and Father Cavanaugh had been in Stuttgart, Germany, when Graham lectured through an interpreter to an audience of sixty thousand. “When we visited the pope three days later, we told him about it. He said he wished he had a dozen such evangelists in our church. When Jack was elected, I told him that one of the first things he should do was to get acquainted with you. I told him you could be a great asset to the country, helping heal the division over the religious problem in the campaign.’†[3]

So what’s happening to Joseph Patrick Kennedy (1888–1969) in these two instances? If we apply Al-farabi’s formulation to these two instances, the first thing to consider is what we interpret Al-farabi to mean by “first ruler.†A literal interpretation would mean George Washington, and one could elaborate and discuss Washington’s deism and any sense of “civil religion†stemming from that which might’ve later been prescribed to the country’s citizenry. A contextual interpretation would mean John Kennedy, and one could elaborate and discuss Jack’s Catholicism and any sense of “civil religion.â€

In the first instance, Kennedy has lost tremendous faith in the administrators of American Catholicism following the election of his son to the presidency.

In the second, we see that, despite that loss of faith, Kennedy still wants what (he sees) as best for American Catholicism, and the best he could see for that Catholicism in 1960 was for it to attempt to reconcile, understand, and begin a dialogue with American Protestantism.

Nearly sixty years later, it is easy to say––particularly with the rise and fall of the Religious Right––that that reconciliation was never absolute. There seem to be more significant divisions within the American Protestantism of 2017 and within the American Catholicism of 2017 than the divisions between the two.

[1] Alfarabi, The Political Writings, Translated by Charles E. Butterworth. (Cornell UP, Ithaca, NY), “Book of Religion†p. 93, § 1.

[2] Nasaw, David. The Patriarch: the Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy, (New York, NY: Penguin, 2012) 724.

[3] Nasaw 757.

January 16th, 2017 — reading

Things Recently Read on Russia, Obama, Democracy, Christianity, & Community

Reshared this week at First Things Magazine is an article where David Novak asked 21 years ago: must community exist prior to democracy? If it does, then it is possible, Novak argues, that the community, particularly the Jewish community, can be religious and its governing democracy secular.

Opposite the idea of several religious communities being collectively governed by a secular democracy is Tolstoy, who sought, in Thomas Larson’s recent words in the Los Angeles Review of Books, “spiritual self-reliance.†And Count Tolstoy finds the best examples of spiritual self-reliance in the lives and beliefs of Russian peasantry—something that espoused by someone today might lead them to later be accused of promoting an ideology of what Tim Strangleman at NewGeography.com this week called “working-class nostalgia.†But, as Strangleman points out, nostalgia tells us more about our attitude toward the present than any understanding we may have (or think we have) of the past.

On the other hand, as Emma Green finds out in the Atlantic Monthly, there are currently some liberals who do not believe outreach toward religious conservatives will be rewarding:

I [Michael Wear, a former Obama White House staffer] think Democrats felt like their outreach [to religious conservatives] wouldn’t be rewarded. For example: The president went to Notre Dame in May of 2009 and gave a speech about reducing the number of women seeking abortions. It was literally met by protests from the pro-life community. Now, there are reasons for this—I don’t mean to say that Obama gave a great speech and the pro-life community should have [acknowledged that]. But I think there was an expectation by Obama and the White House team that there would be more eagerness to find common ground.

Cornel West, who is in some ways a religious conservative, wrote in the Guardian this week a severe critique of the Obama Presidency. More than Obama himself, West focuses his criticism on Obama’s “cheerleaders†who refuse to bear the blame for Hillary Clinton’s defeat as well as the neoliberal economic failures of the Obama administration. On this latter issue West poses the question of whether commercial brands compel their consumers to shun integrity, and he suggests commonwealth of American society in the name of pure profit-seeking. On this last point, it is interesting to compare a passage from Benjamin Nathans’ “The Real Power of Putin†from back in the September New York Review of Books:

The Soviet Union from which Russia emerged in 1991 was the most purpose-driven society the world has ever seen. Yet Laqueur struggles to put his finger on what he calls “the emerging ‘Russian idea,’†partly because so many doctrines are competing for influence (Russian Orthodoxy, Eurasianism, antiglobalism, nationalism), and partly because, as he concedes, the vast majority of ordinary Russians “are not motivated by ideology; their psychology and ambitions are primarily those of members of a consumer society.â€

As Alistair Roberts points out on his blog Alastair Adversaria, whether in Russia or America or elsewhere people hunger for truth, not only in purely rational terms, but hunger for truth in other people. We hunger for truth from the doctor when we ask what’s wrong and we hunger for the perceived truth in our leaders (whether or not the truth is actually there). This doubt of whether the truth is or isn’t there in that particular moment is like the wavering, lingering, roving sense of exile. And as Kate Harrison Brennan has recently written of the Western Christianity’s alleged perception of exile from rest of the participants in secular democracy, she reminds her flock that exile is a temporary condition; it should never be something one is comfortable with; on the other hand, as she expounds on Jeremiah:

The Israelites in exile were not just to tithe their cash crops, or to seek the good of their Babylonian oppressors as neighbours. Instead, they were to pray actively that the city would prosper, even before they did as a community in exile.

August 1st, 2016 — Criticism

Christians in Name Only

Noah Millman goes for the knock out punch in today’s American Conservative:

Donald Trump’s primary victory is the final proof that even the religiously conservative base of the GOP doesn’t really care about things like abortion and gay rights, because Trump manifestly didn’t care about these questions or was actively on the other side from religious conservatives, and yet he won plenty of evangelical Christian votes in the primaries. So voting for Trump out of religious conservative conviction sends a clear-as-day message that Republicans need do absolutely nothing on those issues in order to win religious conservative votes. It is a statement of abject surrender.

October 13th, 2015 — book blogging, fiction, reading

Two passages particularly struck me when rereading Ilyich. The first has to do with the way healthcare workers tend to cross examine the bodies of patients, like lawyers cross-examining the mind of a witness or police interrogating a suspect. Amid an illness, particularly chronic illness, the patient is always on trial:

Ivan Ilyich knows quite well and definitely that all this is nonsense and pure deception, but when the doctor, getting down on his knee, leans over him, putting his ear first higher then lower, and performs various gymnastic movements over him with a significant expression on his face, Ivan Ilyich submits to it all as he used to submit to the speeches of the lawyers, though he knew very well that they were all lying and why they were lying. (Ivan Ilyich, “Chapter 08â€)

It is almost as if Ivan Ilyich––a bureaucrat and son of a bureaucrat, see “Chapters 02 & 03â€â€“–suspects he may die by the bureaucratic ways and means of his doctor. Recently, I had my own health scare, and while everything turned out to be alright, there were nevertheless forms to fill out and receipts to file away. It is not just 21st century Obamacare or British healthcare or Canadian healthcare that piles on the paperwork—Tolstoy had the intuition, imagination, and foresight to see that healthcare and bureaucracy are intimately intertwined, and have been so since at least the middle of the nineteenth century.

And after all the paperwork has been completed, the tests run, and the doctors have finished updating the diagnoses for their patients—after all these barriers of bureaucracy are crossed, the ill individual looks in the nearest mirror and does not recognize the stranger reflecting back:

And Ivan Ilyich began to wash. With pauses for rest, he washed his hands and then his face, cleaned his teeth, brushed his hair, looked in the glass. He was terrified by what he saw, especially by the limp way in which his hair clung to his pallid forehead. (Ivan Ilyich, “Chapter 08â€)

Intricacies of bureaucracy and images of the body—these are what moderns like us, like Tolstoy, and like those around us must deal with when confronted with a crisis of healthcare. But do we Westerners tend to focus more on the image of the body because of two millennia of Christian culture? The American philosopher James Bissett Pratt (1875–1944) seemed to think so when he observed in an essay written thirty years after Tolstoy’s story:

I think, however, there are several additional factors which give Hinduism a certain advantage over Christianity in nourishing a strong belief in immortality. One of them is connected with the question of the imagination already discussed. The Hindu finds no difficulty whatever in imagining the next life, for his belief in reincarnation teaches him that it will be just this life over again, though possibly at a slightly different social level. I am inclined to think, moreover, that the Christian and the Hindu customs of disposing of the dead body may have something to do with this contrast in the strength of their beliefs. Is it not possible that the perpetual presence of the graves of our dead tends to make Christians implicitly identify the lost friend with his body, and hence fall into the objective, external form of imagination about death that so weakens belief in the continued life of the soul? [Bookbread’s emphasis] We do not teach this view to our children in words, but we often do indirectly and unintentionally by our acts. The body––which was the visible man – is put visibly into the grave and the child knows it is there; and at stated intervals we put flowers on the grave – an act which the child can hardly interpret otherwise than under the category of giving a present to the dead one. And so it comes about that while he is not at all sure just where Grandpa is, he is inclined to think that he is up in the cemetery. Much of our feeling and of our really practical and vital beliefs on this subject, as on most others, is of course derived from our childhood impressions.

(“Some Psychological Aspects of the Belief in Immortality†Harvard Theological Review. Vol. 12. No. 3. (July 1919.) 294–314 at 308.)

September 3rd, 2015 — Criticism

Law, Love, and George Christoph Lichtenberg

Over at The American Conservative, Rod Dreher challenges readers:

Traditionalist, orthodox Christians are a minority in this country, and are going to become ever more despised. The day is coming when the only protection many of us can rely on is the law, and the willingness of government officers to obey the law, even though they hate us. And so, my final question … Is the principle that the [Thomas] More of Bolt’s play powerfully elucidates really something we can afford to take lightly?

The majority of Americans, that is, those who don’t happen to be traditionalist, orthodox Christians, hate hypocrisy. And those who hate hypocrisy are the most hardhearted of hypocrites. For as the German sage taught us at the dawn of the Enlightenment:

I am convinced we do not only love ourselves in others but hate ourselves in others too.

–George Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799)

So America hates hypocrisy–and if Herr Lichtenberg’s dictum carries any merit it comes from our country’s evident embrace of those most notorious species of hypocrite: cheaters and liars. Tom Brady has been exonerated for flat footballs, over 300,000 U. S. died in the last 14 years (the Bush-Obama Era) because they were denied (via bureaucratic procrastination) the healthcare promised them, and Ashley Madison appears to be the most successful ponzi scheme since Madoff.

Speaking for the minority of traditionalist, orthodox Christians over at First Things, Carl. R. Truman gets it exactly right today:

I have no reason to doubt [Kim Davis’] sincerity or the significance of her conversion. But the fact that she has only been a professing Christian for a few years scarcely defuses the power of the question. The politics of sex is the politics of aesthetic and rhetorical plausibility and a multiple divorcee understandably lacks such plausibility on the matter of the sanctity of marriage. The only way in which her defense could be deemed plausible would be if the church in general had maintained in practice, not just theory, a high view of marriage. Then the move from outside the church to inside the church would perhaps have more rhetorical power. In fact, at least as far as Protestantism goes, the opposite is the case. The supine acceptance by many churches of no fault divorce makes the ‘I have become a Christian so it is all different now’ defense appear implausible, even if it is actually true in specific cases.

But as Victor Hugo and Ronald Dworkin have pointed out, the law will not save us:

“Everything is legal.â€

–Thénardiers, Les Misérables. 1860. IV, vi, 01

In fact, people often profit, perfectly legally, from their legal wrongs. The most notorious case is adverse possession—if I trespass on your land long enough, some day I will gain a right to cross your land whenever I please.

–“Is Law a System of Rules?” The Philosophy of Law (1977)

And if the law will not save us, we must then turn to love.

September 20th, 2010 — Uncategorized

June 7th, 2010 — education, reading

At the Catholic literary journal Dappled Things, Hugo-nominated sci-fi writer Michael Flynn puts to rest the myth that Christianity held back science during medieval times, and shows how it was rather the opposite that was true:

The philosophers of the “Age of Reason†called the Middle Ages the “Age of Faith,†and claimed that because “God did it!†was the answer to everything, no one searched for natural laws. Some have since imagined a “war†between science and religion, and accused the medievals of suppressing science, forbidding medical autopsies, and burning scientists. Bad times for science and reason!

Or was it? In fact, the Middle Ages were steeped in reason, logic, and natural philosophy. These subjects comprised virtually the entire curriculum of the universities.

Come on: “Steeped in reason, logic, and natural philosophy?” While I have no doubt “these subjects comprised virtually the entire curriculum of the universities” such a suggestion of steepness seems to imply that the majority of Europeans attended universities in the Middle Ages—a steep slope of argument much too slippery for my meager, Middle American footing.

The Age of Faith and Reason » First Thoughts | A First Things Blog.

March 10th, 2010 — Books, education

The dead can be read by all—still, the literary lives of Texans continue to decay.

After reading posts on both the Houston Chronicle‘s Texas on the Potomac Blog, “Poll: 30% of Texans Believe Humans and Dinosaurs Lived Together” and Paul Burka’s “Dispatches in the Evolution“ at Texas Monthly‘s political blog, Bookbread now finds comfort in:

- the certainty that our state’s educational standards will continue to erode.

- knowing that anyone passing through the twenty-first century public school systems of Texas will never produce a work of literature worth reading, or discover a finding in science worth reviewing, or engineer a stack of Lincoln logs worth burning.

- knowing that there’s nothing to be gained by keeping twenty-first century students latched inside the public school systems of Texas.

After reading Russell Shorto’s article of the New York Times: “How Christian Were the Founders?” Bookbread should point out that it doesn’t matter how Christian the founders were, or the amount of Christian-ness that Texans claim the founders had because that great avenger, Apathy, assures us that whatever is taught will not be learned.

After reading an editorial in“Spanish on State Websites“, Bookbread must note: What does it matter? If a fiscally broke state (such as North Carolina or Texas) has no government services to offer its citizens, who cares in what language such denials-of-service come packaged? Aren’t folks free to let Google auto-translate the articulations of government inefficiencies should they feel the need?

After reading Sara Mead at Eduwonk and her article “I Will Avoid Putting a Silly Headline Here About Messing With Texas“:

I tend to agree with Tom Vander Ark that some of the issues specific to the Texas Board of Ed’s ability to dictate the content of the nation’s textbooks through its textbook adoption process will eventually be rendered obsolete by evolutions in digital learning and print-on-demand–which will also be good things more generally for the quality of instructional materials in schools, not to mention children’s backs as they’ll have fewer ginormous [sic] textbooks to lug around.

Bookbread has yet to put his faith in “evolutions in digital learning and print-on-demand“—because regardless of the rate of evolution for digital printing, who’s to say whether such a rate will (or ever has) correlated with the rate of demand for print-on-demand? Who’s to say the rate of demand for print-on-demand products won’t perpetually decrease even as the rate of evolution for digital products continues to increase?

After reading Gary Scharrer of the San Antonio Express‘s “Governor Candidates Silent on School Reform“, Bookbread comprehends how stagnation remains the status quo for the public school systems of Texas. Thankfully, such comprehension comes as no surprise, for we Texans have always cherished our love affair with apathy. After all, both individuals and states cannot remain independent when they lack apathy for others.

January 30th, 2010 — Criticism

One of the first questions that comes to mind after reading Plato’s Ion (380 B.C.E.) is: What is the role of the reciter or “rhapsode†in modern America? According to Plato:

[No] man can be a rhapsode who does not understand the meaning of the poet. For the rhapsode ought to interpret the mind of the poet to his hearers, but how can he interpret him well unless he knows what he means? [01]

On the surface, it seems that Ion, as a reciter, has no equivalent counterpart in our America of the twenty-first century. Once upon a time, the role of the rhapsode was to recite Homer, which, in a sense, was the Hellenic Bible.

Like the ancients, the inhabitants of the information age can lay hold to two general types of reciters: the religious and the secular. Religious ones recite the religious texts of their sect whether Muslim, Jewish, Protestant, or Catholic. Plato confides to Ion:

[For] not by art does the poet sing, but by power divine … God takes away the minds of poets, and uses them as his ministers, as he also uses diviners and holy prophets. [02]

The religious reciter is inevitably a theologian, a word inescapably Greek.

Albert Mohler, a modern theologian and current president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, has recently reported on a British survey in the [London] Times on the state of the kingdom’s preachers. He concluded his post “How Will They Hear Without a Preacher?†(Jan. 2010) by claiming that: “preaching is the central act of Christian worship,” and that the “preaching of the Word of God is the chief means by which God conforms Christians to the image of Christ.” [03]

On the other hand, the Hellenic heritage of Plato holds:

All good poets, epic as well as lyric, compose their beautiful poems not by art, but because they are inspired and possessed … God himself is the speaker, and that through them he is conversing with us. [04]

But what kind of preaching is Mohler interested in sustaining (perhaps reviving) for modern American religious rhaposdes? Principally, Mohler means “preaching that is expository, textual, evangelistic, and doctrinal. In other words, preaching that will take a lot longer than ten minutes and will not masquerade as a form of entertainment.” [05]

If someone should masquerade as a form of entertainment while reciting a text, most modern Americans would label that person (provided they used Bookbread’s diction) a “secular rhapsode.†These Modern, secular rhapsodes recite popular movies, game lines, or popular song lyrics as seen on American Idol. Others come in the form of actors, as when last summer William Shatner recited a speech first given by Sarah Palin.

In ancient times, hundreds of years before the dawn of history . . . a reciter, such as Plato’s Ion, was a middle-man between the true poet and the audience/readership. These true poets (i.e. Homer, Sappho, David, Taliesin) might better be understood as “sub-poets†considering how Plato reduces these rhapsodes to be “interpreters of interpreters,†[06]. Homer, poet a priori, has already interpreted life and thereby created art. Rhapsodes must, in turn, interpret the original interpreter.

Elaboration for this idea of a sub-poet can be found in Dante’s suggestion in the Divine Comedy (1321) where he comments on the arts of man as being the grandchildren of God (Inferno, Canto XI, 103–105):

And, if thou note well thy Physics, thou wilt find, not many pages from the first, that your art, as far as it can, follows her, as the scholar does his master; so that your art is, as it were, the grandchild of the Deity. [07]

Likewise runs Tolkien’s idea of the true poet as a sub-creator, found in his essay On Fairy Stories (1939):

The story-maker proves a successful “sub-creatorâ€. He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “trueâ€: it accords with the laws of that world. [08]

Mohler, moreover, notes in his interpretation of the [London] Times preaching survey:

Evangelicals were most enthusiastic about preaching, while others registered less appreciation for the preached Word. Interestingly, [Ruth] Gledhill reports that “Baptists and Catholics were also more enthusiastic about the Bible being mentioned in sermons than were Anglicans and Methodists.” [09]

Finally, Canadian critic Northrop Frye once observed in The Anatomy of Criticism (1957) how:

Ion, which is centered on the figure of a minstrel or rhapsode, sets forth both the encyclopedic and the memorial conceptions of poetry which are typical of the romantic mode. [10]

There seems to be a bit of romanticism hinted at by Plato when he concludes the dialogue of Ion by asking: “Which do you prefer to be thought, dishonest or inspired?” [11]. Dare it be asked: Can the dilemma of the modern romantic rhapsode be reduced to a question of dishonesty versus inspiration?

[01] Plato. “Ion.†The Dialogues of Plato Translated into English. Trans. B. Jowett. Third Edition. (1892). Oxford UP. Vol. 1. pp. 497.

[02] Ibid. pp. 502.

[03] Mohler, Albert. “How Will They Hear Without a Preacher?†January 20, 2010.

[04] Supra. n. 01, pp. 501–502.

[05] Supra. n. 03.

[06] Supra. n. 01, pp. 503.

[07] Alighieri, Dante. “Canto XI.†Inferno. The Divine Comedy. (1321). Dante’s Divine Comedy: Inferno. trans. by John A. Carlyle. Second Edition. (1867). Chapman & Hall, London. pp. 128.

[08] Tolkien, J. R. R.. On Fairy Stories. (1939). The Andrew Lang Lecture. March 8, 1939. The Monsters and the Critics – the Essays of J. R. R. Tolkien. Ed. Christopher Tolkien. (1983) (2006) Harper Collins. pp. 132.

[09] Supra. n. 03.

[10] Frye, Northrop. The Anatomy of Criticism. (1957). Princeton UP. Tenth Printing (1990). pp. 65.

[11] Supra. n. 1, pp. 511.

January 13th, 2010 — Books, writing

From the Washington Monthly via Little Green Footballs:

As [Texas] goes through the once–in–a–decade process of rewriting the standards for its textbooks, the [Creationist] faction is using its clout to infuse them with ultraconservative ideals.

An unstated assumption in the above article from Mariah Blake implies that well-written textbooks might have a positive effect on the lives of American public school students.

That assumption might hold true for well-written “books” but not for the tautological tangles found in a composite term such as “textbook.” (If a text can exist as a book, and a book can exist a text, a textbook is a tautology, no?)

But even if Blake’s assumption were true, one must still ask: Why not let Creationists and book publishers conduct a social experiment financed by voter’s property taxes? Why not let them run their liberal scheme which uses the public schools for their laboratories? What’s wrong with exercising the determination (even after their savior warned them otherwise, i.e. John 18:36) to built a Creationist publishing kingdom that rules over America’s public schools? Perhaps they are already predestined to try.

The Creationists might all worship the same god, but if they can’t even agree upon which building they want to talk about him in, why should any citizen or student of Texas expect a Creationist-approved textbook to exhibit any kind of moral influence on their behavior and thinking? Even if the textbook in question specifically concerns creation and Christianity, no Creationist textbook editor or team of editors will ever produce anything about American Christianity teachable, memorable, or influential to students because of the religion’s vast and various theologies, denominations, spin-offs, creeds, sects. Students–even those most enthusiastic, most receptive to ANY kind of Creationist and/or Christian eduction–would encounter at best, a gray haze.

Blake further fails to mention that there was never a time in Texas history when some faction wasn‘t:

using its clout to infuse … ultraconservative ideals.

And because Blake seems to assume that some Great Liberal/Progressive Era of Texas once existed, her report can permit such farcical, absolute statements like:

never before has the board’s right wing wielded so much power over the writing of the state’s standards [for textbooks].

When did the right wing not have power in the State of Texas (including power over the state’s standards for textbooks)? Really, when was this?

While Don McLeroy and the Creationists’ liberal experiment stands doomed to fail (predestined, if you will), the rest of the nation can take comfort in knowing that Texas Tradition (or Conservatism, or Creationism, or whatever they’re calling it this week) will continue, will abide, will endure and insure that no graduate of the state’s public school system will ever receive a Nobel Prize for any branch of science or work of literature (much less be nominated). Perhaps that is predestined also.

Surely there are more interesting ways to waste property-taxes other than buying shoddy schoolbooks. Surely Texans have not lost complete creativity in that regard. So first thing’s first. It’s time to say bon voyage to NASA. “Adios, all you asshole astronomers!” because to continue maintaining the National Aeronautic and Space Administration within the State of Texas makes about as much sense as opening up a sausage shop in the middle of Mecca.

UPDATE I:

The context of the post above is limited to the medium of textbooks only. But as John Derbyshire observes over at National Review‘s The Corner, if textbooks can’t quite indoctrinate students, electronic media certainly can:

The Children’s Hour [John Derbyshire]

The Hamas TV channel, those jolly folk that gave us Farfur, the Jew-hating Mickey Mouse clone, are at it again:

Hamas’ terrorist TV channel — which routinely indoctrinates kids by portraying Israelis as ghouls — is launching a new cartoon series that depicts another enemy, the Palestinian Authority police.

A pilot episode shows a toadyish Palestinian officer watching as a Jewish character machine-guns a group of West Bank children to death and drinks their blood. “You killed our children before my eyes,” the officer says meekly. “I will respond with even more peace.”

But wait — who’s this? Why, it’s al-Bahni the purple dinosaur! Come on, sing along now, children. You all know the tune:

I love death, death loves me,

Martyrdom will make us free . . .

UPDATE II: I concede to Blake that an instance of a kind of Great Liberal/Progressive Era in Texas, and probably more progressive than liberal, is mentioned somewhere in Robert Caro’s The Path to Power (1982) (to which I have on loan at the moment). I seem to remember, in the context of LBJ’s first campaign for Congress in TX District 10, someone quoted for the farmers political movement of the Texas Hill Country as having said: Â “You have to remember that Roosevelt was a kind of God around here,” however, in the context of the quote, LBJ was struggling in his campaign despite Roosevelt being “a kind of God” to poor, progressive farmers.