Battle of the Bookmark-and-Read-Later Apps: Instapaper vs. Read It Later.

Bookmark & Read-Later Apps: Instapaper v. Read It Later (Gizmodo)

August 26th, 2010 — reading

8 Writing Tips from C.S. Lewis (ChristianWritingToday.com)

July 5th, 2010 — writing

A very tidy tally from the master of things mediaeval.

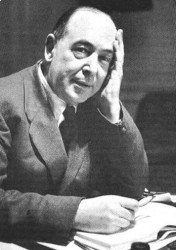

Three Types of Books to Read (Oscar Wilde)

June 22nd, 2010 — Books

Quote:

BOOKS, I fancy, may be conveniently divided into three classes:— 1. Books to read, such as Cicero’s Letters, Suetonius, Vasari’s Lives of the Painters, the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, Sir John Mandeville, Marco Polo, St . Simon’s Memoirs, Mommsen, and (till we get a better one) Grote’s History of Greece.

2. Books to re-read, such as Plato and Keats : in the sphere of poetry, the masters not the minstrels ; in the sphere of philosophy, the seers not the savants.

3. Books not to read at all, such as Thomson’s Seasons, Rogers’s Italy, Paley’s Evidences, all the Fathers except St. Augustine, all John Stuart Mill except the essay on Liberty, all Voltaire’s plays without any exception, Butler’s Analogy, Grant’s Aristotle, Hume’s England, Lewes’s History of Philosophy, all argumentative books and all books that try to prove anything.

The third class is by far the most important. To tell people what to read is, as a rule, either useless or harmful; for, the appreciation of literature is a question of temperament not of teaching; to Parnassus there is no primer and nothing that one can learn is ever worth learning. But to tell people what not to read is a very different matter, and I venture to recommend it as a mission to the University Extension Scheme.

![]()

Oscar Wilde, “To Read or Not to Read”. Originally published in the Pall Mall Gazette, February 8, 1886. The Complete Writings of Oscar Wilde – Reviews. The Nottingham Society. 1909. p. 43. [Google Books]

The Ideal of a Literary Anti-Canon

June 10th, 2010 — Books

Young men, especially in America, write to me and ask me to “recommend a course of reading.” Distrust a course of reading! People who really care for books read all of them. There is no other course. Let this be a reply. No other answer shall they get from me the inquiring young men. [original emphasis]

—Andrew Lang, Adventures Among Books (1905), Longmans, Green, & Co. p. 23.

Mere List Making

January 18th, 2010 — book blogging, Books

At American Fiction Notes, Mark Athitakis lists five reasons for not posting lists of “best books of the year” or any other such lists on his book blog. Bookbread fully supports Athitakis’s proactive approach towards list containment in the book blogosphere even if he has to create lists to do it.

Athitakis also includes some ideas of list making as a potential kind of art form and even spirituality:

Lists contribute to a culture of filthy linkbait whoring that just plays into Arianna Huffington’s greedy goddamn hands. Every person who gets access to a Web site’s stats knows that lists bring in traffic. This is naturally seductive, but ultimately contributes to an online hivemind of short attention spans, which is death on sustained commentary.

All of which is to say that I was a tad cranky.

I might’ve calmed down a little had I read Albert Mobilio’s consideration of Umberto Eco’s book The Infinity of Lists before the holidays. Lists can, he argues, have a kind of art to them, if approached in the right way.

A list is an intimation of totality, a simulacrum of knowing much, of knowing the right much. We select our ten best big-band recordings, all-time basketball starting fives, mysteries to read this summer; add up the people we’ve slept with or people we wish we had; index our movie-memorabilia collection; count our blessings; list reasons for not getting out of bed. We jot these accounts on envelopes, store them on hard drives, murmur them under our breath as we ride home from work—it’s no accident that many prayers are really nothing more than lists.

Bookbread can’t vouch for lists existing as types of art forms — though the listing of statements in Wittgenstein is rather elegant — but when it comes to mental nutrition, there is no doubt that certain lists (in the form of that dreaded c-word “canon”) carry a practicality that cannot be denied. As Harold Bloom observes in The Western Canon (1995), “An Elegy for the Canon”:

Who reads must choose, since there is literally not enough time to read everything, even if one does nothing but read.

The question them becomes: what is the difference between the reader’s choice and mere list making?

[NYR: Umberto Eco]